Evidence-Based approaches to Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

We share the goal of creating a workplace where each person can bring their whole selves to work, but what are the best practices for creating this safe workplace? As psychologists, and as scientists, we have some tools at our disposal to discern which approaches work, and which lead us astray. We’ve learned that essentialist representation of gender and national identity, but not race, is revealed by cognitive demand (Siddiqui & Rutherford, 2021) and that religious labels impact the perception of Christian and Muslim faces (Foglia, Mueller & Rutherford, 2021). Future research may lead us on a path of continuous improvement.

We share the goal of creating a workplace where each person can bring their whole selves to work, but what are the best practices for creating this safe workplace? As psychologists, and as scientists, we have some tools at our disposal to discern which approaches work, and which lead us astray. We’ve learned that essentialist representation of gender and national identity, but not race, is revealed by cognitive demand (Siddiqui & Rutherford, 2021) and that religious labels impact the perception of Christian and Muslim faces (Foglia, Mueller & Rutherford, 2021). Future research may lead us on a path of continuous improvement.

The Psychology of Peace

We know that adults have dedicated cognitive processes that allow for altruism and reasoning about moral judgment. Psychological processes that support moral behavior are part of a suite of social cognitive adaptations that allow us to be a large-group social species, but these processes have only recently been explored empirically. We are exploring developing psychological machinery underlying prosocial and moral behaviour. Maheen Shakil is exploring whether our human psychology allows us to expand our definition of our ingroup, and thus extend our moral concern to a bigger circle. The key to the puzzle is understanding the psychology that motivates aggressive and cooperative decisions.

We know that adults have dedicated cognitive processes that allow for altruism and reasoning about moral judgment. Psychological processes that support moral behavior are part of a suite of social cognitive adaptations that allow us to be a large-group social species, but these processes have only recently been explored empirically. We are exploring developing psychological machinery underlying prosocial and moral behaviour. Maheen Shakil is exploring whether our human psychology allows us to expand our definition of our ingroup, and thus extend our moral concern to a bigger circle. The key to the puzzle is understanding the psychology that motivates aggressive and cooperative decisions.

Showing up as a leader: The perception of transgender people in leadership

As McMaster’s first transgender department chair, Rutherford has had his fair share of challenges. Two years into his term as chair, the university received a report recommending that Rutherford be replaced as chair, because he didn’t “show up as a leader.” This led to some deep curiosity about how transgender and non-binary people are perceived, and whether this perception is compatible with leadership. One project involves the reaction to persuasive text when read aloud by a transgender or cisgender speaker. Is there a difference in how persuasive they are? Another project involves whether transgender and non-binary leaders are perceived as being “special interest” leaders. Are they seen as just representing the interests of trans and non-binary people, or whether the people they lead can see them as representing the broad interests of the group. A third project is designed to study the characteristics of people who do (and don’t) hear it when a trans person is misgendered, as well as the inferences people make when they don’t register that someone has been misgendered. Does failing to hear a pronoun slip lead people to believe that it didn’t happen?

As McMaster’s first transgender department chair, Rutherford has had his fair share of challenges. Two years into his term as chair, the university received a report recommending that Rutherford be replaced as chair, because he didn’t “show up as a leader.” This led to some deep curiosity about how transgender and non-binary people are perceived, and whether this perception is compatible with leadership. One project involves the reaction to persuasive text when read aloud by a transgender or cisgender speaker. Is there a difference in how persuasive they are? Another project involves whether transgender and non-binary leaders are perceived as being “special interest” leaders. Are they seen as just representing the interests of trans and non-binary people, or whether the people they lead can see them as representing the broad interests of the group. A third project is designed to study the characteristics of people who do (and don’t) hear it when a trans person is misgendered, as well as the inferences people make when they don’t register that someone has been misgendered. Does failing to hear a pronoun slip lead people to believe that it didn’t happen?

The Perception of Animacy and Biological Motion

How do people know whether an object is alive? We study the motion cues of animacy, asking what cues people use to perceive that something is animate. We have found that speed matters, but perceived speed matters more (Szego & Rutherford, 2007; 2008). We use point-light walker stimuli to test whether people with autism can perceive simple actions based on these rudimentary cues to biological motion cues (Rutherford & Troje, 2011; Rutherford, Trivedi, Bennett & Sekuler, in prep). A recent meta-analysis revealed that in autism spectrum study samples, biological motion perception correlates with IQ, suggesting the recruitment of broader cognitive processes (Foglia, Siddiqui, Khan, Liang & Rutherford, 2021).

How do people know whether an object is alive? We study the motion cues of animacy, asking what cues people use to perceive that something is animate. We have found that speed matters, but perceived speed matters more (Szego & Rutherford, 2007; 2008). We use point-light walker stimuli to test whether people with autism can perceive simple actions based on these rudimentary cues to biological motion cues (Rutherford & Troje, 2011; Rutherford, Trivedi, Bennett & Sekuler, in prep). A recent meta-analysis revealed that in autism spectrum study samples, biological motion perception correlates with IQ, suggesting the recruitment of broader cognitive processes (Foglia, Siddiqui, Khan, Liang & Rutherford, 2021).

The Perception of Emotional Facial Expressions

We take an evolutionary and functional approach to the study of emotion perception. The relationship between the emotion categories is predicted by their function (Rutherford and Chattha, 2005). Recent work has shown that various methods, including the Visual Expectation Paradigm, can be used to reveal stable and reliable category boundaries (Cheal & Rutherford, 2015). We now know that young children use a more rule-based strategy for emotion perception, but develop a template-based strategy as adolescents (Foglia, Zhang, Walsh & Rutherford, 2021).

We take an evolutionary and functional approach to the study of emotion perception. The relationship between the emotion categories is predicted by their function (Rutherford and Chattha, 2005). Recent work has shown that various methods, including the Visual Expectation Paradigm, can be used to reveal stable and reliable category boundaries (Cheal & Rutherford, 2015). We now know that young children use a more rule-based strategy for emotion perception, but develop a template-based strategy as adolescents (Foglia, Zhang, Walsh & Rutherford, 2021).

The development of autistic characteristics, and the broader phenotype

One prominent question in autism research is what are the very early signs of autism. We know that early diagnosis and early treatment lead to improved prognosis. In an ongoing, longitudinal project, using eye tracking technology, we are recruiting and testing very young siblings of children with autism in order to see whether early social perception can be used to predict a later diagnosis of autism. We observe these infants who are at risk for autism with the aim of detecting the very earliest correlates of a later autism diagnosis and social cognitive development. This has obvious clinical applications as well as having the potential to answer important theoretical questions. We’ve learned that infants developing with ASD show a unique developmental pattern of face scanning (Rutherford, Walsh & Lee, 2015), and that Social Attention is increasingly atypical across the first six months in the broader autism phenotype (Rutherford, 2013).

One prominent question in autism research is what are the very early signs of autism. We know that early diagnosis and early treatment lead to improved prognosis. In an ongoing, longitudinal project, using eye tracking technology, we are recruiting and testing very young siblings of children with autism in order to see whether early social perception can be used to predict a later diagnosis of autism. We observe these infants who are at risk for autism with the aim of detecting the very earliest correlates of a later autism diagnosis and social cognitive development. This has obvious clinical applications as well as having the potential to answer important theoretical questions. We’ve learned that infants developing with ASD show a unique developmental pattern of face scanning (Rutherford, Walsh & Lee, 2015), and that Social Attention is increasingly atypical across the first six months in the broader autism phenotype (Rutherford, 2013).

Brain Response to Emotional and Social Stimuli

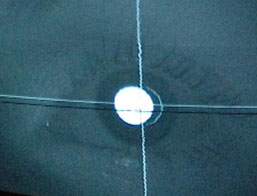

Using Diffuse Optical Tomography, we can measure brain activity in adults and children. We use this to measure the brain’s reaction to social and emotional stimuli. This can tell us what parts of the brain are responsive in those with and without autism, so that we can compare these two groups. We can also use this technology to test whether different people’s brains categorize emotions the same way, and respond similarly to emotionally provocative scenarios.

Using Diffuse Optical Tomography, we can measure brain activity in adults and children. We use this to measure the brain’s reaction to social and emotional stimuli. This can tell us what parts of the brain are responsive in those with and without autism, so that we can compare these two groups. We can also use this technology to test whether different people’s brains categorize emotions the same way, and respond similarly to emotionally provocative scenarios.